The 23rd Psalm.

Written by Dr. Pelham K. Mead II (c) 2014 Western Writers Association.

Books on Sale on Amazon and Kindle.

The 23rd Psalm

2015

The 23rd Psalm is a science fiction novel about when a Comet hits the Earth and melts the South Pole. The Earth floods to the depth of 6,000 feet above sea level covering all the cities of the world except Tibet and other high mountains. There are several themes in this story. First, the survival of a Christian church group and a Jewish Temple group in Lake Tahoe, California when the Earth flooded. They fled to high ground at North Star Mountain and Boreal Ridge. The second theme is the emergence of a Jewish cantor who develops strange powers to see the future. Later on after the Rabbi dies the Cantor become the Messiah for both the Christian and Jewish groups. The third theme is about survival and the importance of never giving up despite the odds.

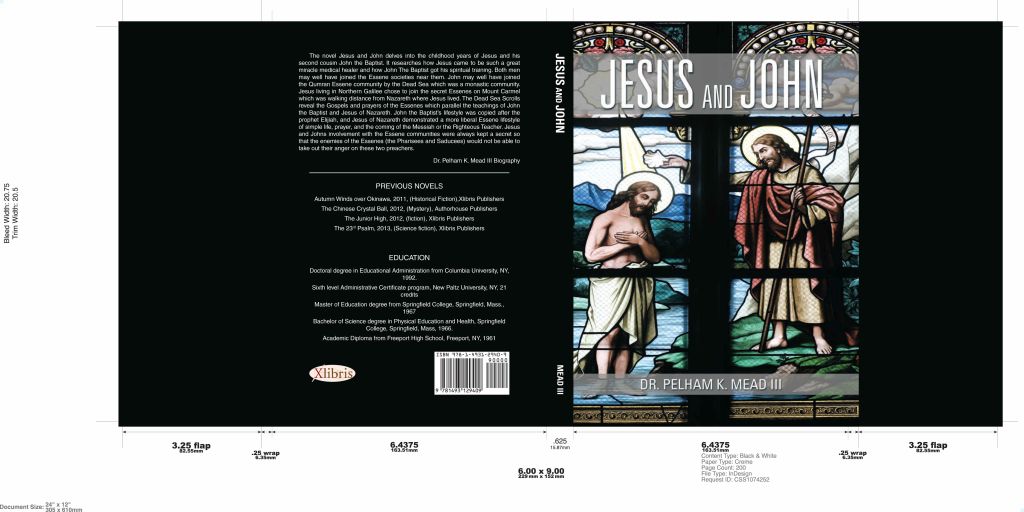

Jesus and John

2016

Based on two years of academic research this book recounts the Holy Family fleeing to Egypt when Herod orders all first born males killed. They flee Herod’s troops for eight years according to the Egyptian Coptic Christian Church verbal and written tradition.

The second part of the book begins with Jesus aka Jeshua son of Joseph of Nazareth at age 12 in the temple. Later on when Jesus’ father Joseph dies when Jesus is around 15 years of age he seeks out the Essenes on Mount Carmel. John Jesus’ cousin was the son of a temple priest and when his father died he went to live with the Essenes living on the Dead Sea in a monastic community. The Essenes taught Jesus and John the importance of baptism. John made it the main part of his ministry. Jesus also followed in John’s path with baptism and more. Much of the research on the Essenes comes from the Dead Sea Scrolls which were written by the Essenes in 70 AD and hidden from the Romans when they destroyed the Jewish temple and the Essene village on the Dead Sea.

Reading improves the mind and frees one’s immigration to lands beyond the horizon.

From the blog

-

Hello World!

Welcome to WordPress! This is your first post. Edit or delete it to take the first step in your blogging journey.